The diffusion equation

The microscopic model

The above-mentioned microscopic models give us exact results without approximations. We can ask: if we relax the fixed step size condition, what could be changed? Let’s start with the one-dimensional case. We use \(r\) to denote the displacement of the random walk with a random step size. The microscopic model can be described as

This expression means once the position of the particle at time \(t\) is known, the particle will move to a random new position \(r(t+\Delta t)\). The microscopic environment is fluctuating wildly, so our reference particle will interact with its environment in a complicated way. We avoid this complication by approximating the coupling of our reference particle with the environment using an effective random displacement \(l\).

The probability distribution function of the random step, \(l\), is \(\chi(l)\). In general, the distribution function can be any function. However, we would like to keep our results as general as possible. Therefore, instead of giving a specific functional form of \(\chi(l)\), we take the opposite approach. We assume \(\chi(l)\) to be any function that satisfies the following conditions:

\(\int \chi(z)dz=1\): It is the normalization condition. We include all the possible results, and the probability is locally conserved.

\(\langle z\rangle=\int z\chi(z)dz=0\): expectation value of the random step is zero.

\(\langle z^2\rangle=\int z^2\chi(z)dz=a^2\): The width of the distribution function is characterized by the parameter \(a\). The requirement that the integral is convergent means the distribution function, \(\chi(z)\) cannot have a slowly decaying tail at large \(|z|\).

The macroscopic question

In the macroscopic world, we rarely keep track of the microscopic motion of the molecules. Instead, it is more convenient to describe the little particles using a function, \(\rho(r,t)\), that describes the density field.

What?

Let’s try to think more carefully about how this field is constructed. As we know, the microscopic particles fluctuate at the microscopic length scale. When we define our density field, we evaluate the density at \(r\) by average the particle number over a length scale \(\delta r\). That is, \(\rho(r,t)=\frac{N_{\delta_r}}{\delta r}\) where \(N_{\delta_r}\) represent the number of particles in \([r-\frac{\delta r}{2},r+\frac{\delta r}{2}]\). How to choose \(\delta r\)? We hope we can choose \(\delta r\) large enough such that \(\rho(r,t)\) is not fluctuating too much. Why should we expect the fluctuation to become small when \(\delta r\) is large enough? Small compared with what? What happens if \(\delta r\) is too small? What do we mean by “not fluctuating too much”? If we perform a similar analysis in time, what does that mean?

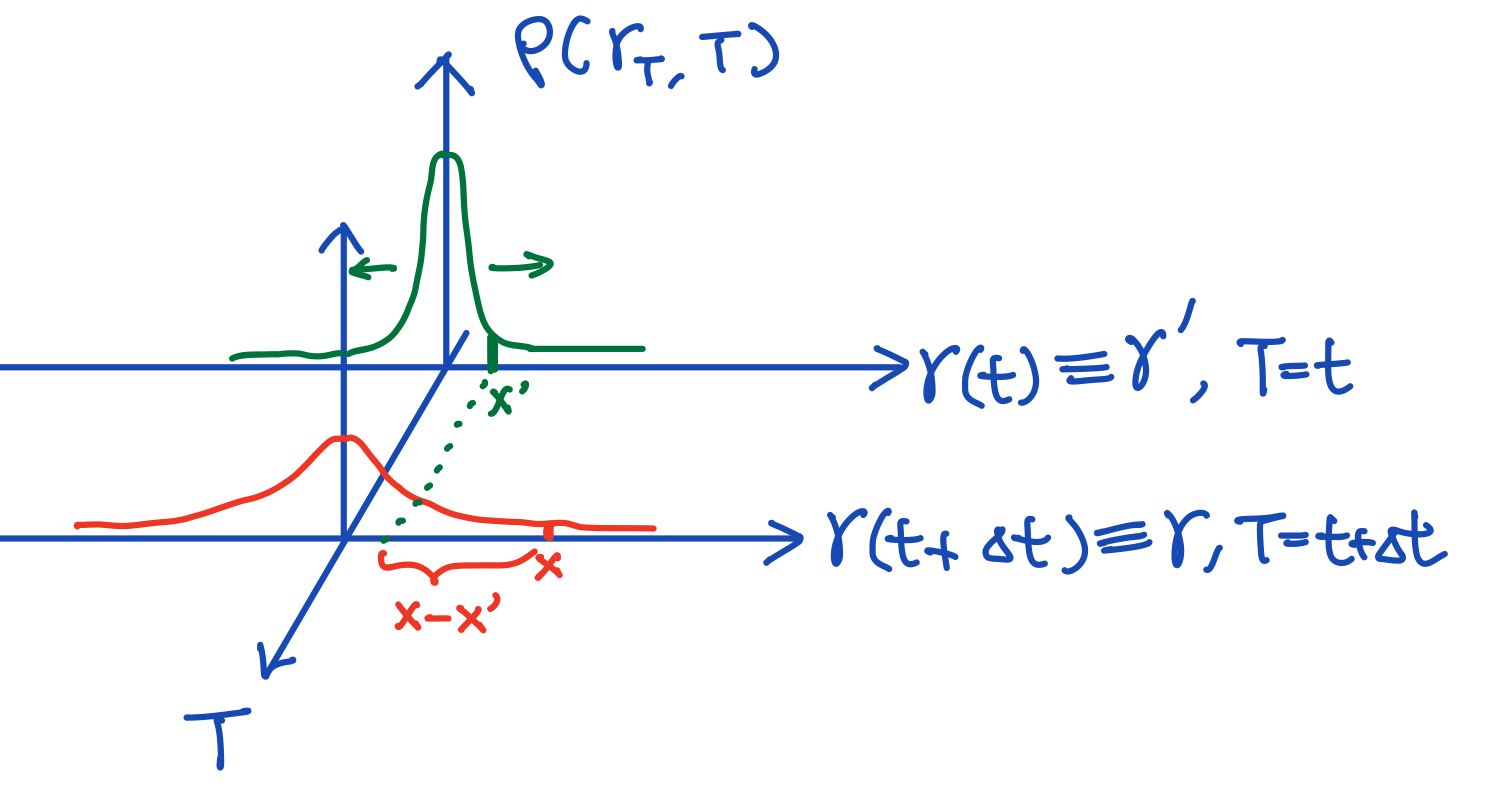

Fig. 7 Evolution of the density field.

The question we would like to understand at the macroscopic level is: how does the density field change as a function of time if the microscopic components are doing the random walk we proposed at the microscopic model?

The density field at \(x\) is described by

Here, we make the change of variable \(z=x-x'\) and

Here, we expand RHS by assuming \(z\) to be small. When \(z\) is large, the probability distribution function \(\chi(z)\) decays very fast. Then we have

Using the assumptions we have made to our probability distribution functions, we can simplify the expression as

The LHS can be simplified as

This relation leads to the diffusion equation

Finally, we have successfully built the macroscopic description using a microscopic model with parameters \(\frac{a^2}{2\Delta t}\).

The diffusion equation can also be derived phenomenologically, where we use \(D\), the diffusion coefficient, to describe the diffusion equation as

The currents and the locally conserved particle number

Consider a one-dimensional system where we pick a segment of length \(\Delta x\). We can ask: what is the change in the number of particles in this segment? A simple derivation gives

When we take the \(\Delta x\to0\) limit, we will have

This expression helps us to understand the current for the diffusion equation. Combining this relation with the diffusion equation, we have

We can integrate this equation from both ends to get the expression of the diffusion current. Here, the constant of integral should be zero since the microscopic model is an unbiased random walk with no background current.

What?

Suppose we have a density profile of the Gaussian function; what is the expression of the diffusion current?

The effect of external forces

When we have external force, we modify our microscopic model as

The additional term, \(F\gamma\Delta t\) is the displacement from a constant external field. We assume the particle’s velocity is zero between the random walk events, the displacement for uniform acceleration motion is

From this expression, we can derive \(\gamma\) as

Here \(\overline{v}\) is the average velocity between \((t,t+\Delta t)\). With similar arguments, we can derive the diffusion equation and the current under the influence of external force to be

and

The solution of the diffusion equation

We would like to understand how the density profile \(\rho(r,t)\) evolve in time and space. It will give us a rough picture of how a system reaches equilibrium. The evolution process toward equilibrium is a complicated process in both classical and quantum systems. The random walk process is the simplest one that can give us a rough picture. We will start from the equilibrium solution, \(\frac{\partial \rho^*(r)}{\partial t}=0\). Then, we will discuss the general solution \(\rho(r,t)\).

What?

We also learn a similar concept, the steady-state. How the idea of equilibrium differs from the idea of steady-state? In this section of the lecture note, I did not distinguish the concept clearly. However, the two ideas are subtlely different.

The equilibrium solution

There are two cases for the equilibrium solution–the case without an external field and the case with an external field. I will discuss both cases.

\(F=0\): \(\frac{\partial {\rho^*}\,^2}{\partial x^2}=D^{-1}\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t}=0\rightarrow \rho^*=\rho_0+Bx\). Here, \(\rho_0\) and \(B\) are the constants to be determined. Suppose we study a system of particles confined by a solid container. At the boundary, the current needs to be 0. This leads to the boundary condition \(J=0=-D\frac{\partial \rho^*}{\partial x_{boundary}}=-DB\). That is, \(B=0\). So the equilibrium solution, in this case, is the homogeneous distribution, \(\rho^*=\rho_0\) is constant.

\(F=-mg\): Consider the case with gravity. We have \(\frac{\partial \rho^*}{\partial t}=\gamma mg \frac{\partial \rho^*}{\partial x}+D\frac{\partial^2 \rho^*}{\partial x^2}\). The solution of this equation is \(\rho^*(x)=A e^{-\frac{\gamma mgx}{D}}+B\). With the boundary condition that the density is zero at the end of the universe, we have \(\rho^*(x\to\infty)=0, B=0\). We have the solution \(\rho^*(x)=A e^{-\frac{\gamma mgx}{D}}\).

Now we know the behavior of the equilibrium solution, we will further tackle the evolution of the density profile for arbitrary time \(t\).

The general solution of the diffusion equation

We will introduce two methods to solve the diffusion equation. The “solution” of the diffusion equation means we know the density profile for arbitrary space-time once an initial condition, \(\rho_i(x,t=t_i=0)\), is given. In general, this process is quite complicated. However, the fact that the diffusion equation is a linear equation simplifies the analysis a lot. The key question we should ask is: are there quantities that are kept fixed during the time evolution? We have learned several conserved quantities in the past. Usually, they are related to the symmetry of the system. The important symmetry for later analysis is the translational symmetry in space. That’s why we will start the analysis from the Fourier method. Once we know how the Fourier method works in general, we will apply that to a special initial condition, the Dirac delta function. We will see the property of Dirac delta function provides a convenient structure to define Green’s function of the diffusion equation. Using the Green’s function, we can construct the evolution of the density profile for arbitrary space-time.

What?

Are the energy and momentum conserved quantities in the microscopic random walk model? In a physical system, should they be conserved?

Approach 1: The Fourier method

Why the Fourier method?

Our system has translation symmetry. We would like to use that property to simplify our analysis. Let \(T_{\Delta}\) denote the translation operator that shifts the system by displacement \(\Delta\). We want to analyze the time evolution of our system; we can use \(U_t\) to express the time evolution of the density profile formally. By definition, we have \(\rho_{k}(x,t)=U_t[\rho_k(x,0)]\). Here, \(k\) is the conserved quantity that is invariant under the time evolution. If such \(k\) exist, it will be helpful for us to analyze the problem. The translational symmetry of our system is equivalent to the following formal expression.

In other words, the result of the shifted density profile after the time evolution from an initial condition, \(\rho(x,0)\), is identical with the time evolution from a shifted initial condition.

Next, we discuss the meaning of the quantity \(k\). If we consider the translation operator as a matrix, then the eigensystem of the translation operator is labeled by \(k\). That is,

If we can find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the translational operator, \(T_{\Delta}\). That will be great! Because we can build the following relation

The above relation says the eigenvalues of \(T_{\Delta}\) is invariant under the time evolution. The next question is: what are the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the translation operator? From the definition of eigensystems, we have

We can just stare at it, and find a simple solution, \(\rho_{k}(x,0)=e^{ikx}\) and \(\lambda_k=e^{-ik\Delta}\). So if we expand the initial condition using the eigenvector, \(\rho_k(x,t)\), the evolution of each component will be labeled by \(k\).

What?

Symmetry plays an important role in physics. Especially, the representation of the symmetry operator helps us to formulate and analyze the problem. In this case, the translation operator forms an abelian group(Which means the order of applying the translation operator is not important). The irreducible representation of the abelian group is one-dimensional. So we can use \(e^{-ik\Delta}\) to represent the translational operator. From the representation theory of the group, we can rationalize where this solution came from. [Tin03]

The solution according to the Fourier method

Now, we know why we want to use the Fourier method to simplify our result. The diffusion equation is a linear equation. In other words, if \(\rho_1\) and \(\rho_2\) are both the solution of the diffusion equation, the linear combination \(c_1\rho_1+c_2\rho_2\) for arbitrary \(c_1\) and \(c_2\) will also be a solution. So if we can use the eigenvectors to expand our general solution, all we need to do is to find the solution for each \(k\) component. The following steps show how the Fourier method works.

We can expand the density profile as \(\rho(x,t)=\sum_k\widetilde{\rho_k}(t)e^{ikx}\).

Insert this expression into the diffusion equation; we found the eigenvectors will not mix with each other. Therefore, we can focus on a single mode \(k\).

We can derive the solution of the above equation as

We can use the \(t=0\) density profile to get \(\widetilde{\rho_k}(0)\).

The solution is

We can see the solution suggests the high wave vector modes will decay exponentially, \(e^{-Dk^2t}\).

The above steps suggest that we need to get \(\widetilde{\rho_k}(t=0)\) by performing Fourier analysis of the density profile at \(t=0\), \(\rho(x,t=0)\). Then, we reconstruct the evolution of the density profile by integration over \(k\). The process can be carried out. However, it will be better if, for an arbitrary given initial condition, we can derive the density profile at an arbitrary space-time point. We will introduce the idea of Green’s function, which serves this purpose.

Approach 2: Green’s function

The method of Green’s function is based on a property of Dirac delta function. That is, we can express an arbitrary function using the Dirac delta function.

Instead of asking how each component of \(k\) evolves as a function of time, Green’s function method asks another question: if the initial profile is a Dirac delta function, how does it evolve as a function of time? We can apply the Fourier method to this special initial condition to answer this question. We define the time evolution of a Dirac delta function to be \(G(x,t)\).

We then use the Fourier method to derive \(G(x,t)\).

\(\widetilde{G_k}(t=0)=\int G(x,t=0)e^{-ikx}dx=1\).

\(G(x,t)=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int e^{ikx}e^{-Dk^2t}dk=\frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi Dt}}e^{-\frac{x^2}{4Dt}}\) is the solution we are looking for.

The time-evolution of arbitrary density profile is

To get the time evolution of a density profile, all we need to do is to input the density profile at time \(t=0\) into the above expression.

Now let’s look at the Green’s function; we found it is a Gaussian function with standard deviation \(\sigma(t)=\sqrt{2Dt}\). From our previous simple model, we know \(D=\frac{a^2}{2\Delta t}\). Then we got \(\sigma(t)=\sqrt{2\frac{a^2}{2\Delta t}t}=a\sqrt{t/\Delta t}=a\sqrt{N}\) which is equivalent with the \(N\)-steps random walk with step size \(a\). To some extent, Green’s function having a function form of a Gaussian is closely related to the central limit theorem. The central limit theorem suggests the sum of independent variables has a probability distribution function that converges to a Gaussian. We will prove the central limit theorem in our homework 1.

Approach 3: Dimensional analysis

Solving the diffusion equation means we want to know the time evolution for an arbitrary initial condition. Let’s assume that there is a length scale, \(l\), for the initial condition. For example, one can consider a Gaussian with width \(l\). i.e., \(\rho(x,t=0)=\frac{A_0}{\sqrt{2\pi l^2}} e^{-x^2/2l^2}\).

Let’s develop the dimensional analysis and see how it helps us to solve the diffusion equation. Let’s use the notation \(\left[ O \right]\) to denote the dimension of \(O\). We immediately realize

We can use the above parameters to form dimensionless parameters

In principle, we should have the relation

Here, we try to develop the so called similarity solution. That is, we assume the length scale of the initial condition \(l\to0\). The similarity solution corresponds to the case that the limit has no non-trivial effects and the above relation can be replaced by

The power of similarity solution is: we eliminate one dimensionless parameter immediately. With the powerful but bruit force assumption, we can immediately have the relation that

At this moment, we don’t know what is \(f_s(\xi)\). We can insert it into the diffusion equation. Then we have

with the boundary condition that \(\lim_{|x|\to\infty}f_s(x)\to0\).

From the conservation law, we know

Also, the differential equation of \(f_s(\xi)\) suggest it is an even function, which means \(f_s'(0)=0\).

This suggests

Some coefficients in the above derivation is wrong for educational purpose. Please went through the derivation and fix the coefficients for your own.

What we know and what we don’t know…

Now we know how to solve a diffusion equation and how it reaches equilibrium. However, for generic closed classical or quantum systems, how the system reaches equilibrium is still an open question. We will not elaborate more on this fascinating research problem. Instead, we will refer our readers to other sources that discuss these interesting topics ( see, e.g. Thermalization and many-body localization, see [Sre94] and [NH14] )