One dimensional random walk

The coin-flipping game

Let’s start our discussion by understanding the results of successive coin flipping sequences. Suppose we have an unbiased coin that has an equal probability of \(\frac{1}{2}\) to have heads or tails. To simplify our mathematical analysis, we can use a variable \(l_j=+1,-1\) to denote the outcome, heads or tails, of the \(j\)-th flip. In each trial, we flip the coin \(N\) times. So we can use a binary sequence, \(\{l_1,l_2,\cdots, l_N\}\) to represent the result of the trial. So the first question we can ask is: how many different results could we get? The answer is simple; we will have \(\underbrace{2\times2\times\cdots\times2}_{N\text{ of them}}=2^N\).

The binary sequence is not very informative. We can ask a further question: what quantity should we calculate to know something about those results? One quantity is

\(S_N=\sum_{j=1}^N l_j=\text{number of heads}-\text{number of tails}\).

By evaluating \(S_N\), we immediately get some information: whether we have more heads or more tails. When \(S_N>0\) we have more heads; when \(S_N<0\) we have more tails. The value of \(S_N\) thus can be considered as a simple but useful property for the \(k\)-th trial \(\{l_j^{(k)}\}\).

Now, if we have \(M\) trials, we have \(k=1\sim M\). What statistical statement can we make when \(M\) is a large number?

What?

What do we mean by \(M\) is large? How large is large enough?

One of the simplest statistical quantities is the average or the expectation value of \(S_N\). We will use the notation \(\langle A \rangle\) to denote the average or the expectation value of \(A\). Mathematically, it is defined as

We can evaluate a simple example when \(N=1\).

Immediately we can notice \(\langle S_N\rangle=0\) even when \(N\neq1\) because we have equal probability for \(S_N>0\) and \(S_N<0\). \(S_N\) gives us the information whether we have more heads or tails. \(\langle S_N\rangle=0\) tells us that the probability to have more heads is equal to the probability to have more tails.

Walking back and forth

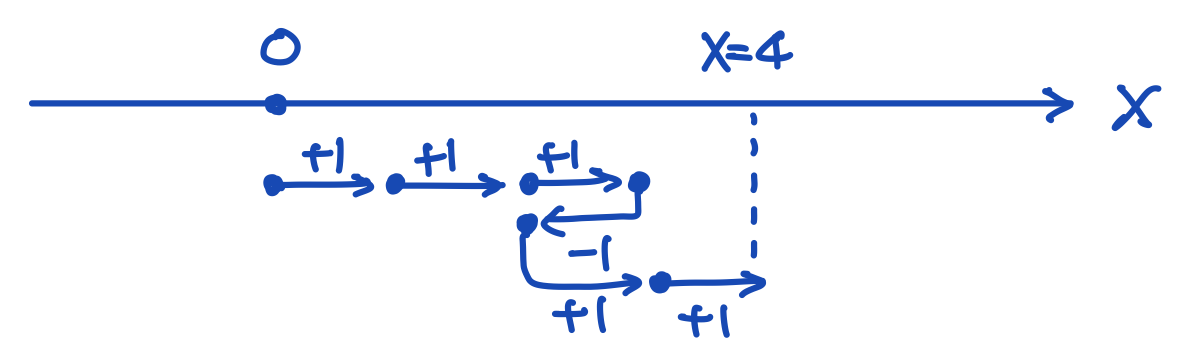

Now, let’s try to twist the coin-flipping game a little bit. Suppose we hold a coin and move on a one-dimensional line starting from the origin. We decide our move according to the result of the coin-flipping game. When we got heads, we moved forward; when we got tails, we moved backward. Here we define \(X_N=S_N=\sum_{j=1}^N l_j\) just to remind ourselves that we are discussing the position after \(N\) steps.

Fig. 5 One-dimensional random walk.

According to the coin-flipping game, we know the expectation value of our position is 0. In this setting, we immediately realize the useful quantity to characterize our motion is the distance with respect to the origin after \(N\) steps. We can evaluate the expectation value of the absolute value of our position, \(\langle |X_N|\rangle\). Or, equivalently, we can evaluate the expectation value of the square of our position, \(\langle X_N^2\rangle\). The root mean square(r.m.s.) of \(X_N\), \(\sigma_{X_N}\equiv\sqrt{\langle X_N^2\rangle}\), is a measure of how far away we are from the origin after \(N\) steps.

Again, it is always helpful to evaluate some of them to have a feeling about what \(\langle X_N^2\rangle\) is.

Similarly, one finds \(\langle X_3^2\rangle=3\). It is very tempting to ask: can we show \(\langle X_N^2\rangle=N\) in general? The answer is yes, we can use mathematical induction. (Assuming the conclusion is true for \(s-1\), we want to prove it is also true for \(s\).)

That is, we assume

is true. We want to show that \(\langle X_s^2\rangle=s\) using the above assumption. We can show that easily by noticing

\(\langle X_{s-1}l_{s}\rangle=0\) since the result of \(l_s\) is independent of \(X_{s-1}\). Therefore, the product has an equal probability to be positive or negative.

So we know the r.m.s. of \(X_N\) is \(\sigma_{X_N}=\sqrt{\langle X_N^2\rangle}=\sqrt{N}\).