Thermodynamics as an effective theory

Reference: [Pel11] Chapter 2 and [Set21] 6.4

What is thermodynamics?

Thermodynamics is a phenomenological theory. Phenomenological theory means it is based on observed phenomena or based on experiments. However, the microscopic question such as why the macroscopic system behaves in a specific way given we assume how the microscopic components interact with each other is not within the describability region of a phenomenological theory.

What phenomenological theory provides is the relation between different macroscopic quantities. For example, we will discuss energy, temperature, pressure, volume, particle number, chemical potential, free energy, etc. . Of course, those quantities are related to each other by several equations. Thermodynamics provides a framework to start from a minimum set of axioms such that we are able to derive the core relations and use them to construct various relations between those quantities that we need to explain our experiments.

The logic is like we have a set of experiments; we might construct some relations using this particular set of experimental data. Then, we apply the set of rules to other systems. Of course, this set of rules could work or fail. If it works, we keep it into our phenomenological theory. If it doesn’t, we try to find ways to fix it by including other rules. After exploring a huge set of experiments, we reformulate our theory by finding physical arguments to keep the core relations. We iterated this process for a long time; now, we have the thermodynamics in our textbook that can be applied to various systems.

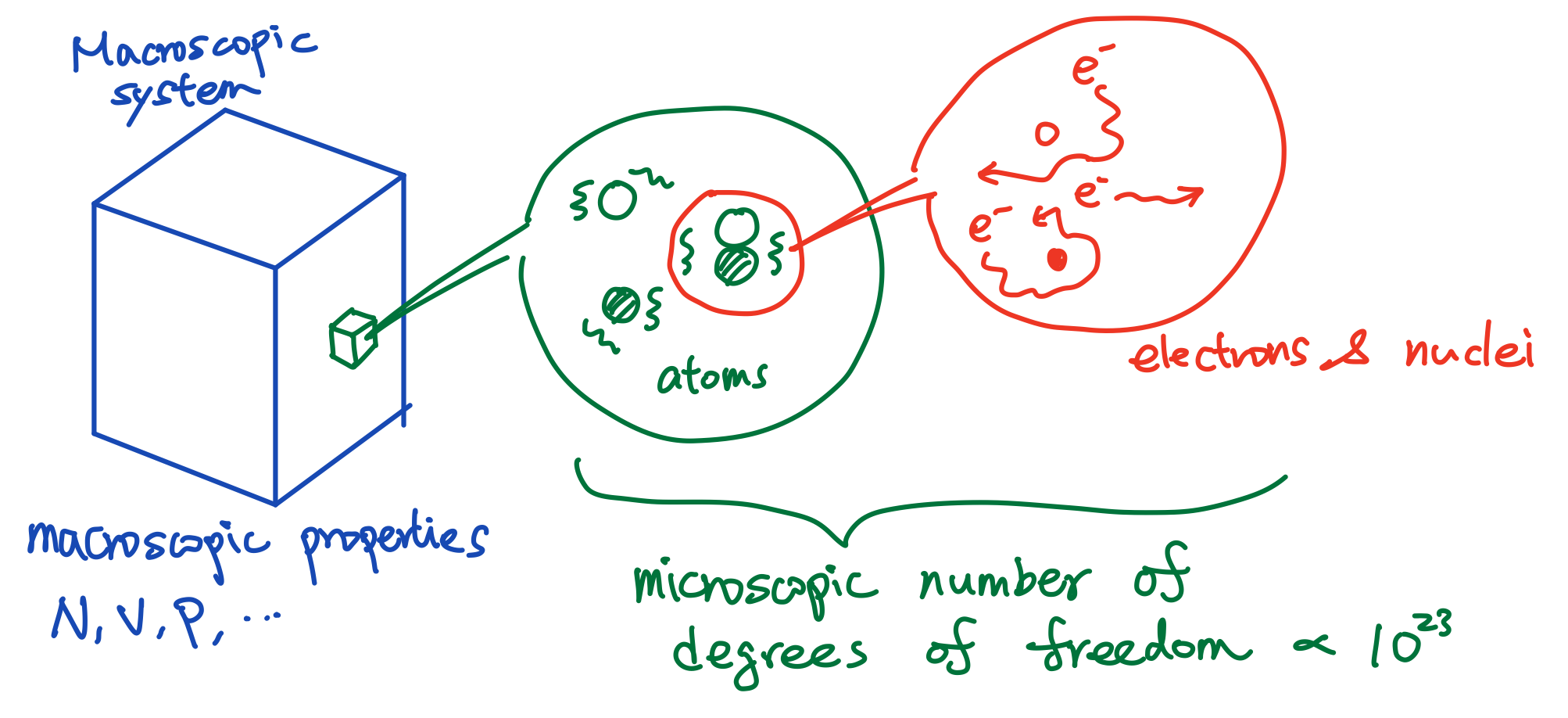

Fig. 1 The microscopic physics and connection with macroscopic physics.

How to go from microscopic to macroscopic?

Different systems might have very different microscopic descriptions. Therefore, going from microscopic physics to macroscopic physics also varies. It is usually challenging to derive the macroscopic expressions from microscopic theories. The challenge lies in the microscopic degrees of freedom that interact with each other Fig. 1.

In this course, as many textbooks did, we will start from the idealized limit where the microscopic theory is “simple” in the sense that they do not have interaction. Those models are usually too naive to describe real physical systems. However, the non-interacting limit allows us to go pretty far and make an explicit connection with the macroscopic observables. In that sense, they are very useful for us to formulate abstract ideas in statistical mechanics. We will formally describe the idea of statistical mechanics and use those non-interacting systems to build some intuition about the meaning of the system.

Once we know what happened in non-interacting systems, we can use them as a starting point to treat the interaction effects through mean-field treatment or perturbative pictures. With those examples, it helps us to develop a picture of how we can go from microscopic theory to macroscopic description, at least in principle.

Of course, those examples are introduced because they are tractable and well studied. There are more interesting systems that are still under active research. We will not be able to cover them all. I will try to mention some of them during the lectures.

Microscopic theory, statistical mechanics and macroscopic observables

I mentioned microscopic theory in the last section. What does it mean? The definition of microscopic physics is not very sharp. Usually, in condensed matter physics, what we mean by microscopic refers to the scale below or around atomic scales. For example, when we study the thermodynamic property of salt (\(NaCl\)), the microscopic degrees of freedom will be the ions \(Na^+\), \(Cl^-\) and the electrons surrounding them. In practice, understanding those degrees of freedom is still quite challenging. The nuclei of \(Na^+\) and \(Cl^-\) will interact with electrons. The nuclei could oscillate. The electrons could interact with each other, etc.

At the microscopic scale defined above, we are facing a quite complicated system. There are at least three families of degrees of freedom: the nuclei of \(Na^+\), the nuclei of \(Cl^-\) and the electrons. All of them are interact with each other. Even worse, we are talking about \(10^{23}\) of them. How should we analyze a system with such high complexity?

There are at least two routes:

Find a good computer and try to use the computational power to understand the complicated behavior of the system.

Make some approximation. When we drop some information, maybe we will be able to analyze the problem. Then we compare with experiments to see if the approximation we made at the very beginning makes sense.

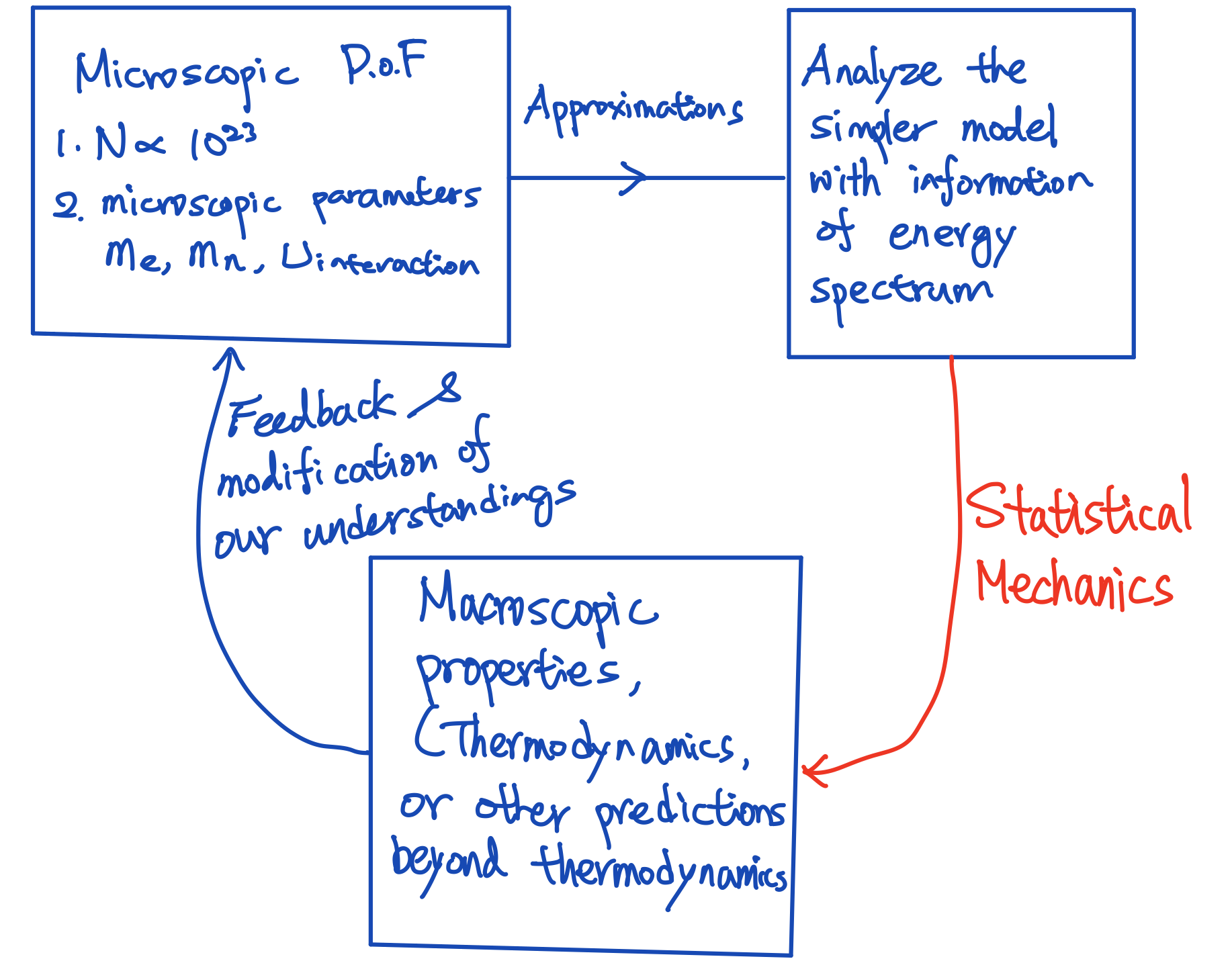

How to proceed using different routes is related to condensed matter physics, so I am not going to elaborate on them further. The point is, no matter which route we take, we will eventually get the information of the energy spectrum if the approach works. Depending on our approach, the spectrum might be discrete, or it might be continuous. The energy spectrum we derived will depend on the microscopic parameters that characterize the system. With the information of the spectrum(derived with various routes), statistical mechanics provides a protocol to convert that information into the macroscopic measurable quantities such as specific heat, magnetization, etc. Then one can compare our calculations with the real experiments and see if we can learn something from the experiments to construct what happened at the microscopic scale. The result will not be identical to the experiments since we usually need to make certain approximations to proceed. The difference between our calculation and the experiments provides hints on improving our approximation or abandon the theoretically proposed microscopic picture. By iterating this process and comparing the experiments and theoretical predictions back and forth, we will eventually reach some conclusion, if we are lucky.

Fig. 2 How statistical mechanics helps us understanding the physics at microscopic level.

That means statistical mechanics provides a way to extract finer information about what happened at the microscopic scale. That is very helpful for us to develop a picture that can bridge the macroscopic behavior using microscopic pictures Fig. 2.

The astonishing part of thermodynamics is that we can describe the macroscopic system using relatively few physical quantities. Regularity emerges out of a macroscopic number of degrees of freedom. It is not obvious that we could find a way to describe the essential information of the macroscopic system with \(10^{23}\) degrees of freedom. A theory that captures the essential physics of the system with relatively small sets of physical observables is the effective theory of our complex system. It means we can understand the complex system effectively using our effective theory. Effective theory and the concept of emergent phenomena form the backbone of modern condensed matter physics and have profoundly influence other research fields. We will discuss the concept of emergent phenomena in the next section.

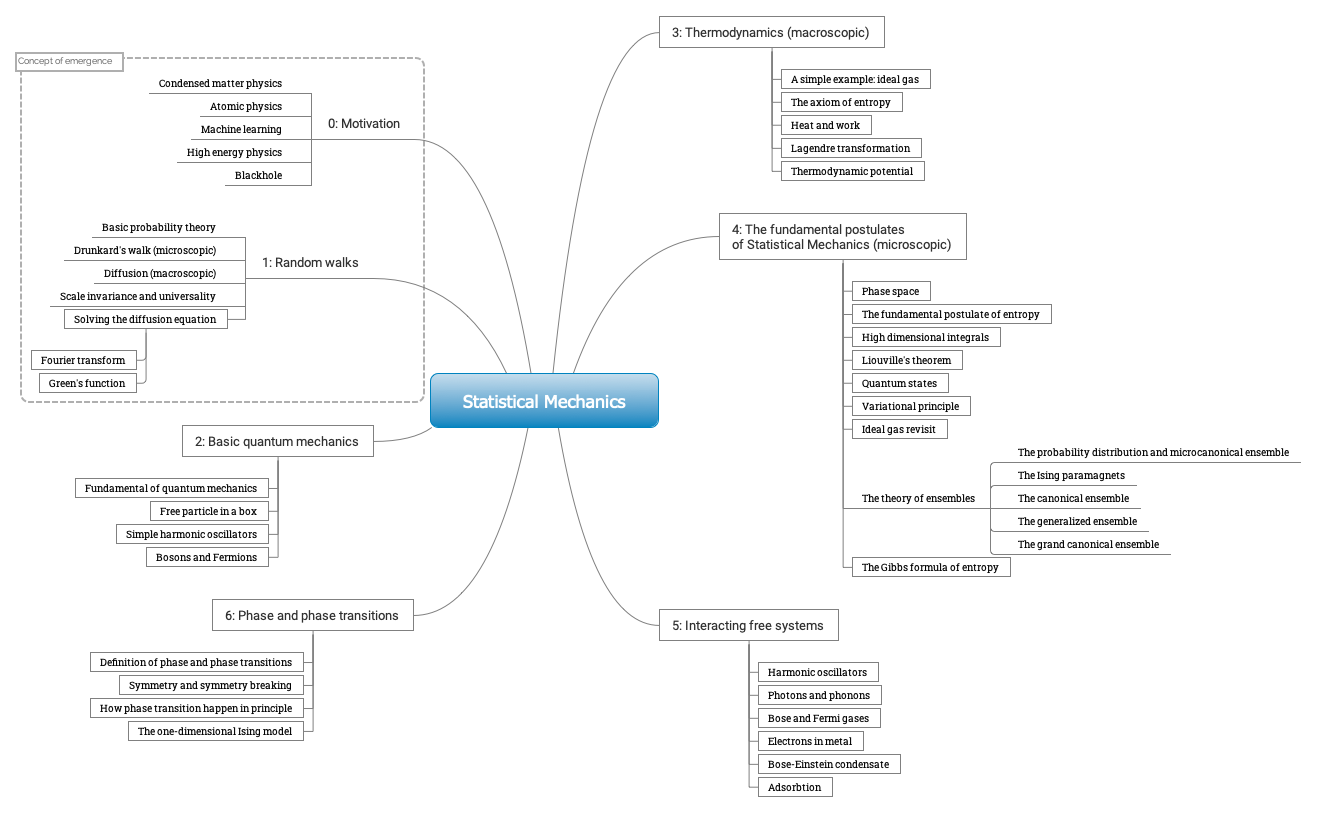

Fig. 3 The roadmap of the course!

The road map of the course is described in Fig. 3.